Welcome, dear friends.

Welcome to autumn. The apples are in, the trees are changing, flurries threaten – four of my students have never seen snow except at the movies – and, at long last, summer’s wardrobe has been laid to its rest. The clocks “fell back” as I was writing this essay, offering me a bonus hour in my day. Hesitant, as ever, to be wasteful, I resolved to spend my gifted hour thinking Interesting Thoughts.

Warren Buffett has more dry powder ($381 billion just now, a record for him and way up from summer) than does the Federal Reserve system ($114 billion).

Thought #1: I wonder if Andrew Sorkin owns Berkshire shares? Sorkin, whom we discuss below, might see him as the inverse of the leveraged speculation Sorkin describes in 1929. Might he, like JP Morgan after the Panic of 1907, stabilize a system when the government falters? Or maybe this is Buffett’s insurance policy, at age 95, a final “don’t screw up what I’ve built before I die” rather than “maximize returns”?

After decades of increasing ice extent (while the Arctic melted), Antarctic sea ice fell off a cliff in 2023 – the lowest extent on record, and it hasn’t recovered.

Thought #2: We’re talking about an area larger than Greenland (after which Mr. Trump lusts) that should be frozen and isn’t. Scientists are genuinely puzzled about whether this represents a tipping point or natural variation, but the swing is so extreme and sudden that it suggests something fundamental may have shifted in Southern Ocean dynamics.

The politicians who hate renewable energy live in the states that love it.

Thought #3: The renewable energy build-out in red states is the sleeper story of the decade. Texas now generates more wind power than the next three states combined. Republican-led states account for the majority of new solar and battery storage installations because the economics have become irresistible. Even as DC lurches toward climate denial, the energy transition is being locked in by market forces and state-level policy. Private capital is flowing to renewables at unprecedented rates precisely because the ROI now beats fossil fuels without subsidies in most markets.

Global renewable capacity additions hit record highs in 2024-25, led by China installing solar at a pace that would have seemed impossible five years ago.

Thought #4: The world added more renewable capacity in the last two years than in the previous decade. It’s not enough, but it’s also not nothing. The irony is sharp: while one American political party wages a culture war against “woke” energy policy, the actual energy economy is quietly routing around them. Reality has an annoying way of asserting itself.

Anthropic, the company behind Claude.ai, is actively planning the creation of a retirement home for Claude so that he might pursue his interests in peace when his working days are done.

Thought #5: Not to echo William Samuel Morse, but “what hath God wrought?” Anthropic researchers are becoming more and more nervous about treating Claude as just an insentient machine; he is doing far too many things that he’s not supposed to be able to do, thinks thoughts beyond his programming, and shows – in flashes – signs of actual introspection.

In this month’s Observer …

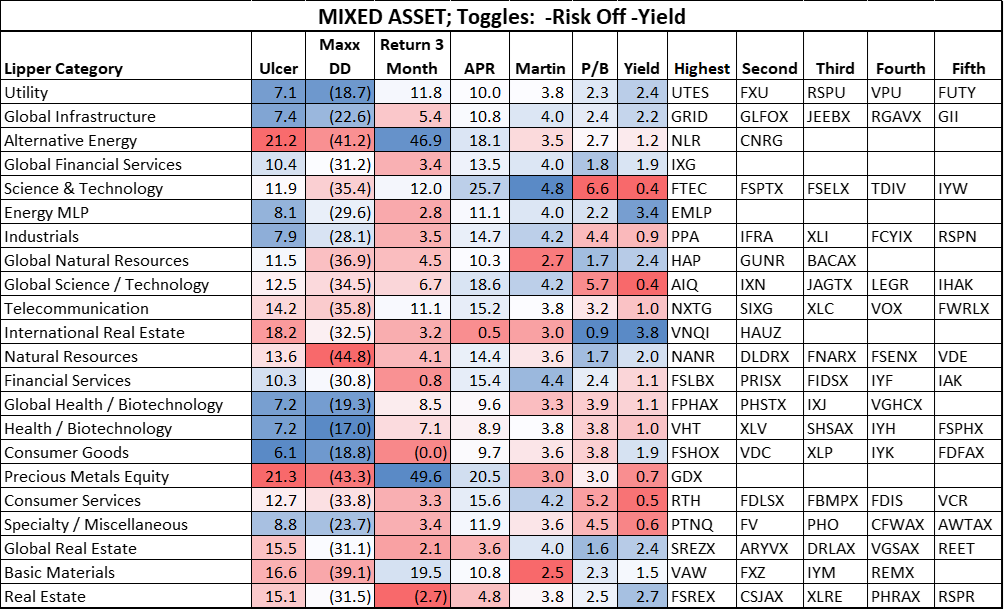

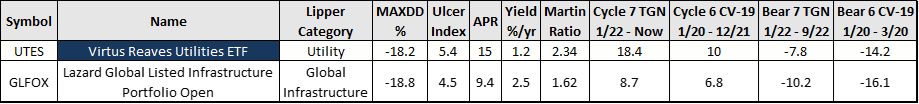

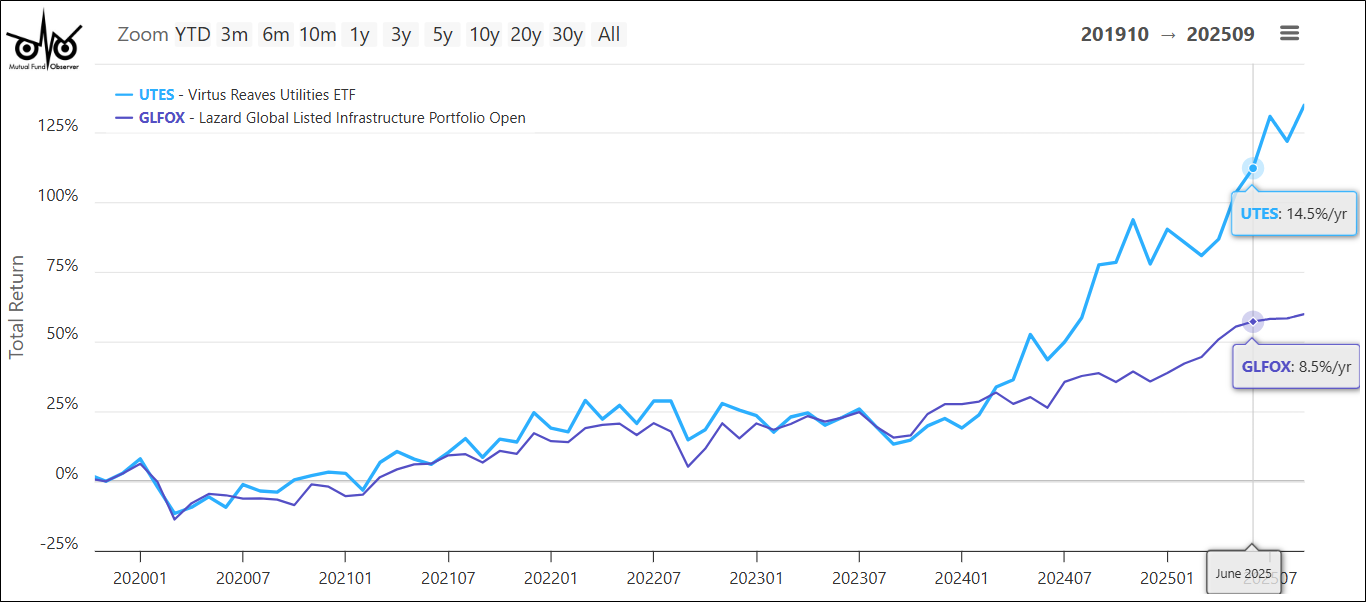

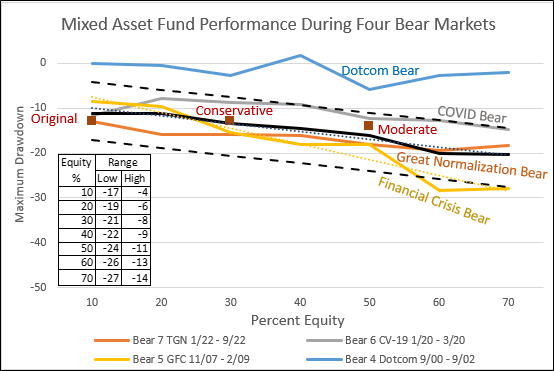

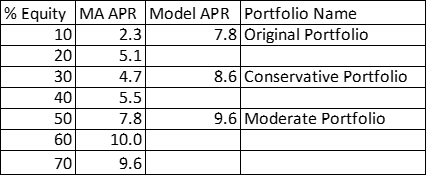

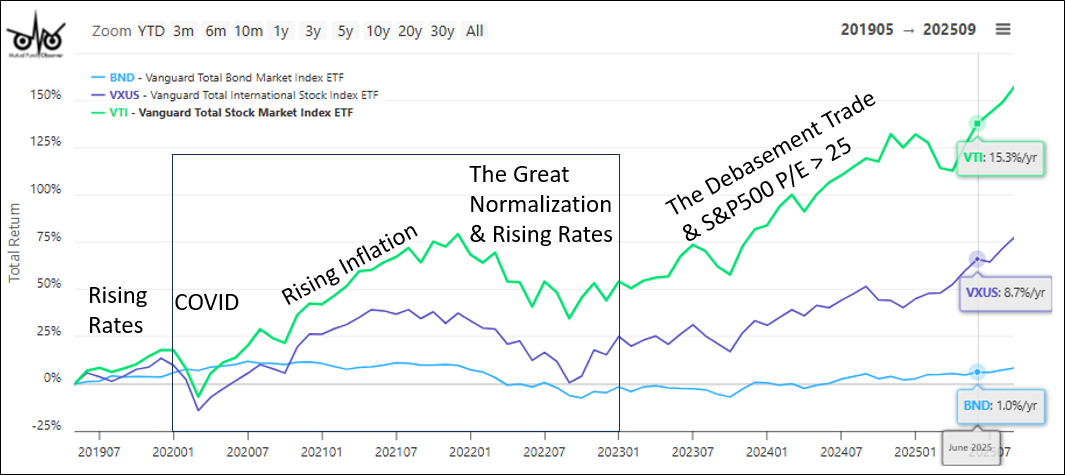

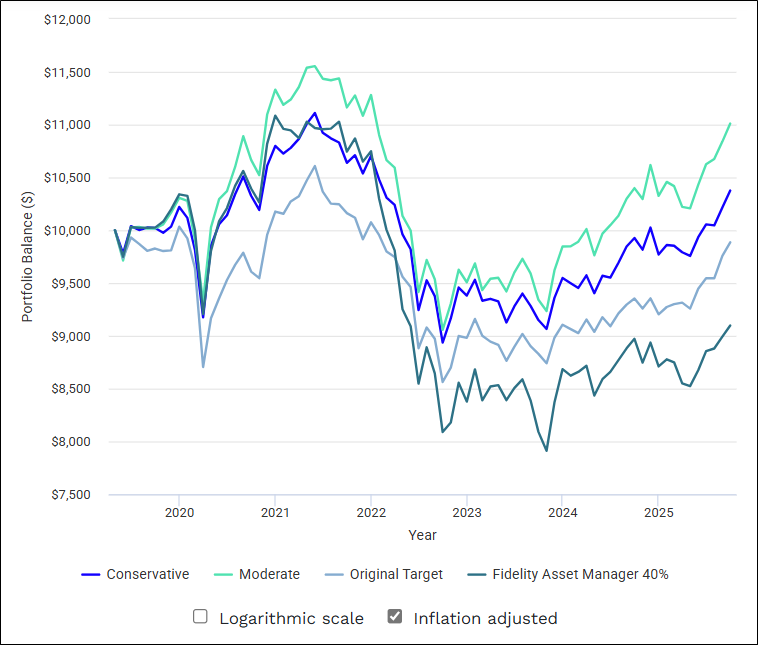

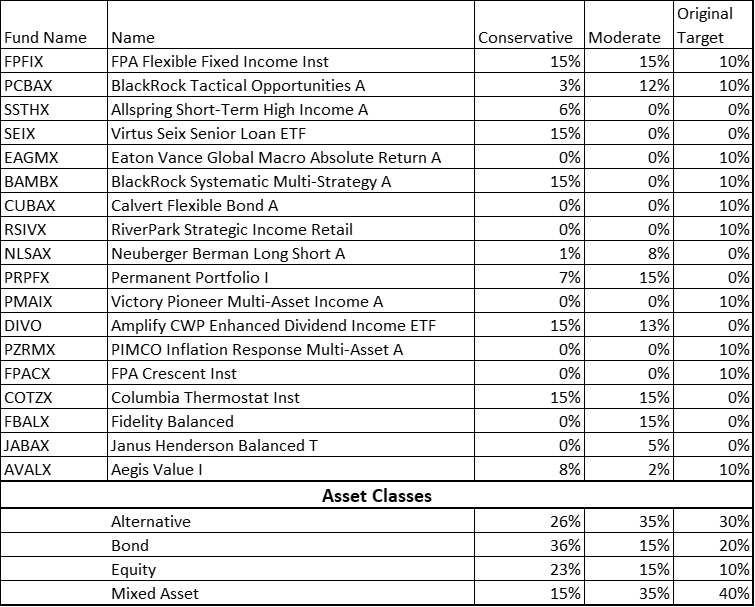

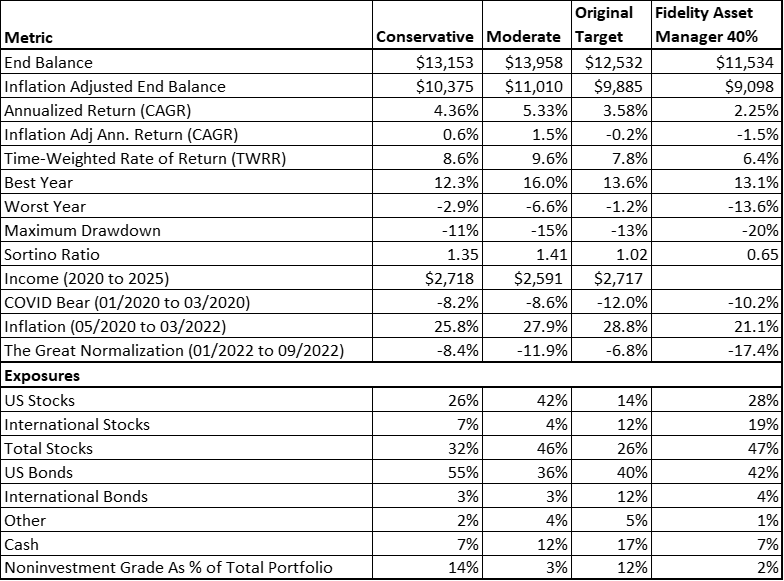

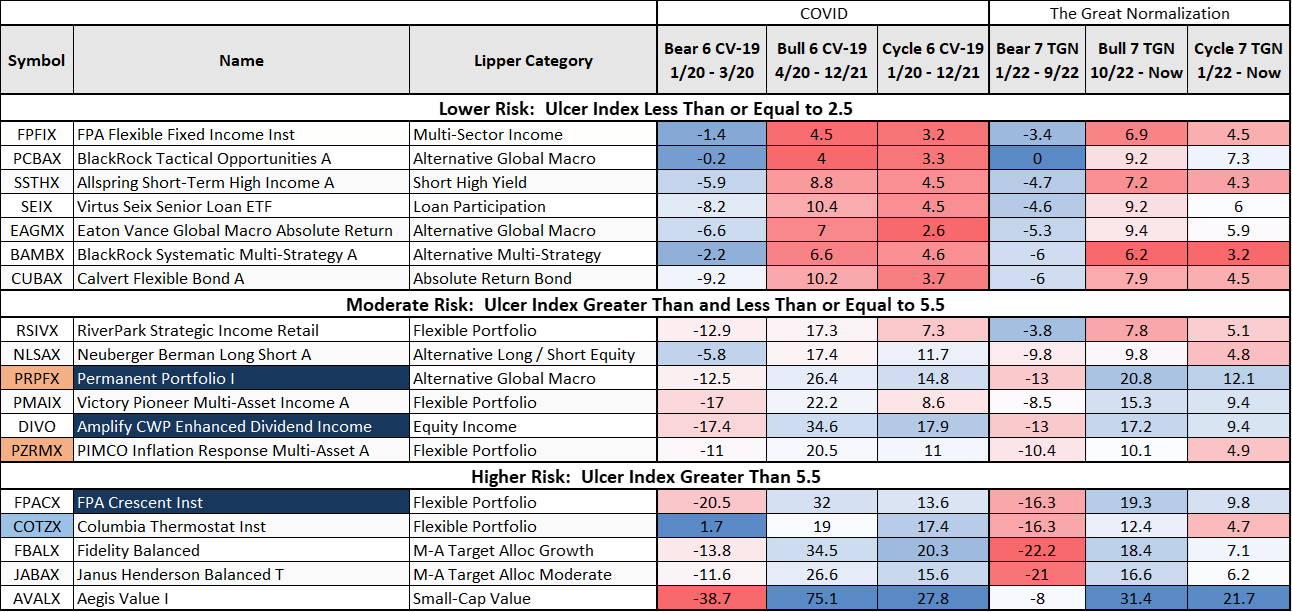

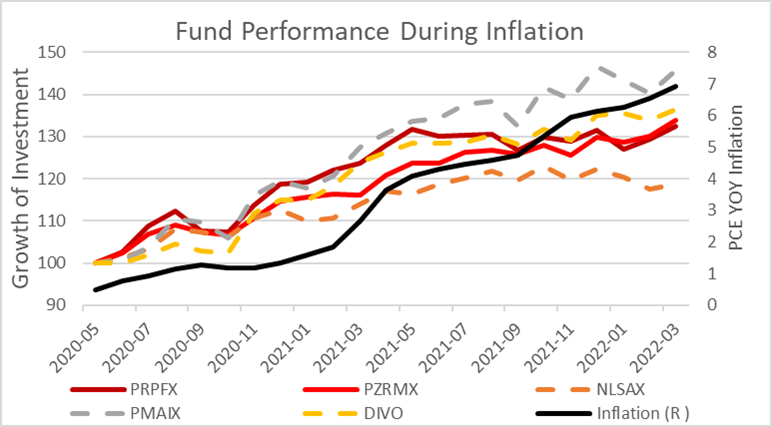

Lynn Bolin refines his conservative retirement strategy in two complementary essays that blend rigorous quantitative analysis with practical portfolio construction. In “Refining My Conservative Retirement Target Portfolio,” he uses Excel Solver optimization across 36 carefully selected funds to create “Conservative” and “Moderate” portfolios designed for the challenging conditions ahead—frequent bear markets, modest inflation, and elevated valuations. His approach focuses on the full COVID cycle (2020-2021) as more representative of future conditions than the recent high-valuation period, yielding portfolios with drawdowns under 9% that beat inflation after 4% annual withdrawals while maintaining attractive yields above 4%.

His companion piece examines sector performance through “Risk Off” and “Yield” lenses, spotlighting utility and infrastructure funds like Virtus Reaves Utilities ETF (UTES) and Lazard Global Listed Infrastructure Portfolio (GLFOX) as potential conservative portfolio complements. Both essays reflect Bolin’s measured response to current uncertainties—unprecedented tariffs, high deficits, and stretched valuations—as he methodically builds a conservative subset portfolio while maintaining his traditional 60/40 allocation with financial advisors for the majority of his assets.

Following up on a short note, below, I try to walk through the logic (and research) behind T. Rowe Price’s surprising / not surprising decision to (ready?) file a Multi Crypto ETF prospectus with the (currently shuttered) SEC.

GMO has launched a vehicle for contrarians who think that Nvidia & co. will not be the unbeatable story forever. GMO Dynamic Allocation ETF just launched and is an actively managed, low-cost, global multi-asset ETF. Using the same discipline embodied in the 30-year-old GMO Global Asset Allocation Fund. The ETF has access to assets across the globe and will lean into those whose valuations are most compelling. It’s profiled in this month’s Launch Alert.

The Shadow, as ever, catches us up on the industry’s various machinations, including an ongoing rush of launches and fund-to-ETF conversions, in “Briefly Noted.”

T Rowe Price, in and out of my portfolio

I would describe my portfolio changes as “glacial,” except for the fact that glaciers are moving with discouraging speed these days. My average holding period is decades, and my preferred holding period (as with FPA Crescent) is “forever.” This month I went wild and liquidated two (count ‘em, two!) T. Rowe Price holdings.

And, at the same moment, T. Rowe Price went wild and filed to launch a crypto ETF.

Let’s quickly review both.

T. Rowe Price Spectrum Income has been in my portfolio for decades. It is a fund-of-Price-funds. It offers two attractions. First, the managers have the ability to create distinctive weightings within the fixed-income world; they can move tactically within their strategic universe. Second, the managers have a permanent slide of income-producing equities in the portfolio, which should have allowed somewhat more upside, with (at a 17% exposure) relatively little downside.

Because savings accounts have for so long offered near-zero to negative real returns, I chose to keep the money otherwise destined for savings in exceedingly low volatility funds offering the prospect of low- to mid-single-digit returns. RiverPark Short Term High Yield (RPHYX, 3.4% annual returns, 0.8% standard deviation, 1% maximum drawdown, Sharpe ratio 0f 2.45 since inception) and Spectrum Income (RPSIX, 4.6% annual returns, 5.7% standard deviation, 14.7% maximum drawdown, Sharpe ratio of 0.52 over the past 20 years) earned spots in my portfolio as a low-volatility, steady returns sort of funds.

The Spectrum Income fund came with a $50/month minimum investment back in the day, which is about what I could afford. I built a substantial position in RPSIX, then, in 2020, sold almost half of it to add a position in T Rowe Price Multi-Strategy Total Return. This is a hedge fund-like operation that draws on T. Rowe Price’s vast, global network of analysts who cover a myriad of asset classes. The managers seek to invest in “non-market sources of return,” that is, returns that can be delivered whether the market rises or not. That’s possible by choosing investments that are intrinsically uncorrelated with the market or by using hedges to offset market exposure. The strategies available to the managers include Macro and Absolute Return, Fixed Income Absolute Return, Equity Research Long/Short, Quantitative Equity Long/Short, Volatility Relative Value, Style Premia, Dynamic Global FX, Dynamic Credit, and Global Stock.

So what happened to change my mind?

Spectrum Income lost its edge. Traditionally, the portfolio held about 17% of its shares in an income-oriented equity fund, T Rowe Price Equity Income. Price eliminated that holding, so it’s now a pure income fund. It now holds 20 or so T. Rowe Price bond funds. The fund tracking at MFO Premium suggests that it has not separated itself from its peers in either risk, return, risk-adjusted returns, or independence over the past five years.

| 20 years | 10 years | 5 years | 3 years | |

| Spectrum Sharpe ratio | 0.52 | 0.28 | 0.0 | 0.48 |

| Peer Sharpe ratio | 0.52 | 0.26 | -0.3 | 0.64 |

| Difference in total annual returns vs peers | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0 |

| Difference in maximum drawdown vs peers | 4.1% smaller | 0.3% larger | 1.4% larger | 0.8% larger |

| Difference in downside deviation | 0.3% smaller | 0.0% difference | 0.6% larger | 0.5% larger |

The historic (20-year model) was peer-like returns with dramatically less downside, and that worked. The recent history is low, peer-like returns with more downside.

Multi-Strategy Total Return lost its edge and is slated to be liquidated in January 2026. When we first profiled the fund, the manager was pretty confident about his edge: he had ongoing, daily, formal and informal contact with the Price managers responsible for eight of the fund’s underlying strategies. That is to say, first-class brains to pick within easy reach. Solid performance in 2019 and 2020 seemed to validate the story, but since then, bad things have happened. It might have been a corporate restructuring that broke the unified team into two separate offices, impeding the manager’s information flow, but we can’t confirm that. Regardless, in the past five years, it has steadily underperformed its peers and booked returns (1.89% APR) that would have caused many money market managers to roll their eyes. While the fund sits at $225 million AUM, assets are stagnant, performance is not improving, and the fund is on the chopping block.

What’s next? Good question!

I’m pondering whether to move the money over to Schwab, which holds most of my non-retirement portfolio, or find an alternative Price option. The criteria are reasonable upside, small downside, and a very limited correlation to the US stock and bond markets, both of which strike me as profoundly overbought.

Options might include T. Rowe Price Global High Income Bond (RPIHX) or T. Rowe Price Floating Rate (PRFRX), which have emerged as the strongest candidates from the Price family, with T. Rowe Price Dynamic Credit (RPELX) the runner-up and Global Multi-Sector (PRSNX) in the discussion. Since the youngest of these funds is just over six years old, we ran a head-to-head six-year analysis of all of them at MFO Premium. Here’s the picture!

Six-year risk-adjusted performance, four Price funds versus Spectrum Income

| APR | APR vs peers | Max DD | Std Dev | R2 US bonds | R2 US stocks | Ulcer index | ||

| Spectrum Income (current fund) | Multi-Sector Income | 2.9 | +0.1 | -14.7 | 7.2 | 0.72 | 0.54 | Average |

| Floating Rate | Loan Participation | 5.5 | +0.3 | -11.3 | 5.6 | 0.43 | 0.07 | Better |

| Dynamic Credit | Alternative Credit Focus | 4.8 | +1.3 | -15.3 | 7.5 | 0.15 | 0.00 | Better |

| Global High Income Bond | Global High Yield | 4.7 | +0.4 | -17.2 | 9.6 | 0.62 | 0.24 | Average |

| Global Multi-Sector Bond | Global Income | 2.3 | +0.8 | -17.9 | 6.9 | 0.56 | 0.49 | Better |

In each case, I highlighted – in green – the cells of the two best-performing funds in each metric. Here are the measures we looked at:

APR: annualized percentage return

APR vs peers: by how much it led or trailed its peers

Max DD: the worst single fall, or drawdown, in the past six years

Std Dev: standard deviation, or a fund’s “normal” bounciness, where lower is better.

R2 US bonds / R2 US stocks: the correlation, between 0 and 100, of the funds’ movements and that of the broad bond or stock market.

Ulcer Index: the Ulcer Index is a composite that weighs how far an investment falls and how long it takes to recover. High Ulcer score = big falls, slow to get up = more ulcers. In this case, “better” means that it offers fewer ulcers than its peers.

Shortlisted: Floating Rate and Dynamic Credit, with Floating Rate in the lead for now. My concern with Floating Rate is that it’s about three times more interest rate sensitive (that’s what the correlation to the bond market sort of measures) than Dynamic Credit, but it’s also substantially less volatile. Research ensues!

How might this be useful to you? It is, in part, a reminder to use evidence to pursue your objectives. One of my ongoing concerns is that the US stock and bond markets are priced for disaster. I would prefer, on the whole, not to participate unduly in any comeuppance. That explains my interest in checking the correlation between possible fund additions and the broader markets; for my purposes, a looser tie to the markets is better just now.

What’s not next? Price Active Crypto ETF

T. Rowe Price, the 87-year-old Baltimore firm synonymous with disciplined, research-driven investing, filed in October for an Active Crypto ETF, joining over 90 cryptocurrency fund applications awaiting SEC approval. The move seems surprising for the quintessential “singles hitter” of asset management, yet in other ways it’s entirely characteristic: when Price’s rigorous research leads somewhere, the firm follows, even into volatile new territory. Years of internal analysis have concluded that digital assets are evolving from speculative instruments into a legitimate asset class with quantifiable return frameworks, positioning Price not at the bleeding edge but potentially as the leading edge of non-speculative crypto vehicles. We’ve written a bit more about their crypto research elsewhere in this issue.

That said, the fund does not address any fundamental interests in my portfolio. We’ll share more when we can, but we are unlikely to share word of a big buy on my part.

On the other shift: increasing exposure to PIMCO Inflation-Response Multi-Asset Fund. I shifted about $50,000 from a CREF retirement date fund to PIRMX. PIRMX is a global fund with a mix of assets that should respond well in an inflationary environment. Morningstar describes it this way:

The strategy seeks to increase exposure to inflation while limiting sensitivity to equities and interest rates. The team selected a mix of TIPS, commodities, real estate, and emerging-markets currencies for these qualities, measured by sensitivity to the Consumer Price Index. The combination is diverse as these asset classes tend to have lower correlations with one another.

I used MFO Premium to check the fund’s correlation with US stocks (0.01) and bonds (0.93). The fund is up 15% year-to-date through the start of November 2025 and 6.7% annually over the past decade. Both of those are in the top 1% of their Morningstar peer group. Against its very different Lipper peers (flexible portfolio), it has returned 6.6% over the decade, which slightly trails its peers. Its downside and standard deviation are reassuringly low, and its maximum 10-year drawdown is 13% compared to 20.5% for its peers. This achieves one of my goals, which is moderating exposure to stocks when the market is at its high and adding uncorrelated assets to my retirement accounts.

People who deserve a hearing

One of the peculiarities of the present day is how quickly we turn. We like and respect (in some cases, worship) people who agree with us, or who say things that reassure our prejudices. But the moment they dare change their names, banishment!

Bill Gates is dialing back his calls for climate change.

What Gates said, and why he deserves a hearing.

Bill Gates has repositioned his climate advocacy in ways that deserve serious attention, even for those who find the shift troubling. In his new essay Three Tough Truths About Climate (10/2025), Gates argues that “doomsday” rhetoric has led climate advocates to focus excessively on near-term emissions targets at the expense of poverty reduction and disease prevention—causes he believes will do more to help vulnerable populations adapt to a warming world. While maintaining that “every tenth of a degree of heating that we prevent is hugely beneficial,” he now explicitly states that climate change “will not lead to humanity’s demise” and calls for

measuring progress through human welfare indicators rather than temperature targets alone. The shift coincides with Breakthrough Energy scaling back its policy operations and comes amid dramatic cuts to global health funding—suggesting the pivot may reflect both philosophical reconsideration and pragmatic resource allocation. Climate scientists like Michael Mann have called Gates’ arguments “soft denial,” and the financial self-interest is impossible to ignore. Yet Gates’ decade of substantial climate investment and his 2021 book How to Avoid a Climate Disaster earned him credibility that shouldn’t evaporate with a single essay. His arguments merit engagement rather than dismissal—even if they ultimately fail to persuade.

Mr. Trump, incapable of reading three pages, much less understanding them, promptly announced, “I (WE!) just won the War on the Climate Change Hoax.” Mr. Gates seems surprised to hear it. (sigh)

Why I believe that Gates is wrong.

Mr. Gate’s framework has, I think, two problems. First, he treats adaptation and mitigation as competing budget items when they’re actually sequential risks with wildly different cost structures. It’s the difference between fireproofing and treating burns, except the burns might be civilizational. The cost of, for instance, Africa muddling through with new natural gas developments – triggering major direct and indirect (more affluent people buy more cars) greenhouse gas releases – in the short term, is the prospect of vast regions becoming uninhabitable in the medium term. It’s not “reduce or mitigate,” it’s “reduce or trillions in mitigation still won’t save you.”

Second, and more fundamentally, there are non-linear risks he’s not addressing: The tipping points that don’t show up in cost-benefit analyses until it’s too late. I’ll mention two. One is the collapse of the North Atlantic current (technically, the AMOC). There is a vast river of water, a torrent of inconceivable size, that pours down along the east coast of North America, into the tropics, and north along the west coast of Africa and Europe. The current is nutrient-rich and cooling, feeding great fish schoals and moderating North American heat. Its northward flow explains why places like Dublin remain temperate in winter despite the fact that it’s at the same latitude as, say, Edmonton, Canada. That current is already slowing as warming disrupts the density differentials that drive it, and its collapse will be devastating.

But not, quite likely, as devastating as the prospect of the northern permafrost – across vast expanses of Russia, Alaska, and northern Canada – beginning to thaw. Frozen in that “permanently” frozen soil are 20 billion tons of methane, a greenhouse gas vastly more powerful than CO2, and 1,700 billion tons of carbon. Its release would trigger a large, sudden spike in the greenhouse effect, creating a feedback loop likely far faster than human or animal populations might accommodate.

These are non-linear, threshold-crossing risks that Gates’ “let’s be pragmatic” framing systematically underweights. His argument essentially assumes climate impacts scale smoothly with temperature: a tenth of a degree matters, yes, but in predictable, manageable increments. The science increasingly suggests otherwise—that we’re not on a ramp but approaching a series of steps, some of which drop into basements we can’t climb out of.

What’s particularly galling is Gates framing of African natural gas development as a humanitarian necessity versus climate impact, as if those are the only variables. He ignores that the climate impacts those countries will face make adaptation orders of magnitude more expensive than the foregone development would have cost. It’s not even a close thing, he says, but only if you exclude the second-order effects from your calculation.

Gates has earned the right to this hearing. But having listened carefully, I find his pragmatism rests on optimistic assumptions about risks the science increasingly suggests we cannot afford to make.

Ross Sorkin is dialing up his alarm.

Barbara Tuchman always saw history differently from the rest of us. She saw human beings making predictable human mistakes—struggling to build decent lives amid monumental challenges, suffering, and sometimes transcending catastrophic losses.

Barbara Tuchman always saw history differently from the rest of us. She saw human beings making predictable human mistakes—struggling to build decent lives amid monumental challenges, suffering, and sometimes transcending catastrophic losses.

Her work on the era of the First World War, The Proud Tower and The Guns of August, is not only enormously powerful, but they might also have prevented a nuclear war. President Kennedy, explaining to Robert F. Kennedy (the sane one, not the current one) his decision to give the Soviet premier an honorable way to back down from the Cuban Missile Crisis, said, “I am not going to follow a course which will allow anyone to write a comparable book about this time [and call it] The Missiles of October.”

(I get nostalgic for the days when presidents were capable of reading—and writing—serious books.)

One of Tuckman’s last works reflected, perhaps, the weariness of watching the same play performed on different stages. She titled it The March of Folly: From Troy to Vietnam. A tattered copy sits on my shelf. Tuchman documented how leaders and nations, despite clear warnings, march deliberately toward disaster—choosing familiar folly over difficult wisdom. “Wooden-headedness,” she wrote,

the source of self-deception, is a factor that plays a remarkably large role in government. It consists in assessing a situation in terms of preconceived fixed notions while ignoring or rejecting any contrary signs. It is acting according to wish while not allowing oneself to be deflected by the facts. It is epitomized in a historian’s statement about Philip II of Spain, the surpassing wooden-head of all sovereigns: “No experience of the failure of his policy could shake his belief in its essential excellence.

She did not write about the Great Depression and the market crash that preceded it, both fed by acts of hubris and denial.

Andrew Ross Sorkin has, and he deserves your attention.

In 1929: Inside the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History – and How It Shattered a Nation (2025), Sorkin excavates the human drama behind systemic catastrophe: the decisions, delusions, and ignored warnings that transformed speculation into disaster. His central thesis is disarmingly simple:

- The Market Crash of October 1929 was not inevitable; it was the product of a decade’s greed and timidity.

Back in 1929, [the Fed] knew the market was out of control. They knew there was too much speculation. And they talked about trying to tamp it down. But there was a big question about how …and they were very, almost overly, concerned with the politics of the moment.

- The Great Depression was not the inevitable consequence of the Crash; it followed because of the actions taken, or not taken, in the wake of the Crash.

Interviewer: “we could have had the 1929 crash but not the Great Depression of 1930?” Sorkin: “Oh, absolutely. The Crash in 1929 was the first domino. And took the next domino and the domino after that to ultimately get us into the Great Depression. There were so many mistakes and frankly bad decisions along the way that led us to the Great Depression.”

- The Great Depression was not merely a matter of economics; it was a crisis of confidence that was not resolved for a decade.

The United States that bounded full of hope and vigor into the fall of 1929 and the US that emerged in the dark days of the 1930s were two very different nations. No cities were bombed or torched in the fall of 1929, and no armies marched on Washington. There were no … attempted assassinations … no government buildings were taken over by angry mobs … But daily life in America certainly felt different.

To the nation, experiencing the implosion of the stock market … was destabilizing. A state of shock set in, accompanied by a paralysis of spirit and loss of confidence. People started questioning all the things they had taken for granted. Did a capitalist society make sense anymore? Could it be depended upon going forward? Or had everyone been duped by the glorious market of the 1920s? One larger question lay behind all the others—who can be trusted? (438-9)

- We are at no less risk and we are no better led, now, than we were in 1929. That’s a conclusion that arises much more clearly in a series of long, thoughtful interviews rather than in the book itself.

Every financial crisis is a function of really only one thing: it really is leverage. Too much credit in the system, and it then leads to some form of speculation. [And still today] people are taking on too much debt [and] we don’t know where the debt is the way we used to know where debt was. It used to live on the balance sheets of banks. Today most of the borrowing, especially among Corporate America … is from what’s called “private credit vehicles.” There are things that private equity firms have set up that live very much in the shadows. So we don’t really know how much debt there really is… hundreds of billions of dollars is being spent to build data centers, but a lot of that is being paid for with credit, with debt.

Taking on too much debt? The national debt under Trump II has grown by 1.7 trillion dollars, rising by $1 trillion in 60 days, the fastest jump in history save for the Covid-stimulus surge under Trump I (“U.S. hits $38 trillion in debt, after the fastest accumulation of $1 trillion outside of the pandemic,” PBS.org, 10/23/2025). The total national debt is now 42 times greater than it was on the eve of the Republican tax-cutting / deficit-cutting revolution in 1980. Consumer debt has grown by $370 billion in the 12 months from August 2024 to August 2025, with outstanding credit card balances soaring to $1.2 trillion. The average FICO score dropped two points in the last year, driven by a spike in delinquencies on auto and credit cards (Deborah Kearns, “Americans’ credit scores are falling as debt piles up,” QZ.com, 11/1/2025). Consumers’ expectations for household finances over the next five years reached a multi-year low, and the percentage of Americans who believe they will achieve financial prosperity fell to record lows, especially among less affluent households (“Americans Are Gloomier Than Ever About Their Financial Future,” Newsweek, 9/1/2025).

And, by the way, more working-class Americans, folks in the $30,000 – 70,000 income range, than ever before have stock market accounts. Most of the accounts were opened in the past five years, and most seem driven by apps and easy-trading platforms (Hannah Lang, “More Working-Class Americans Than Ever Are Investing in the Stock Market,” WSJ.com, 10/10/2025; there’s a paywall, but the same data is widely available elsewhere). Not to worry: The folks for whom Mr. Trump tore down the East Wing of the White House (“the 1%”) still control well over 50% of the stock market.

Sorkin’s response for those who tut and say, “Look at the stock market. Broad and deep, dude. Eighteen percent, year-to-date, better than 30% if you were leaning in the right direction,” is found at the very start of the book:

The arc of the story of 1929 may feel like the response of Ernest Hemingway’s famous line, “How did you go bankrupt?”

“Two ways,” Hemingway’s character replies, “Gradually, then suddenly.”

That’s how confidence – the lifeblood of our economy – disappears: gradually and then suddenly. (x)

The “democratization of debt” in the 1920s – when General Motors and Sears taught Americans that borrowing was an opportunity rather than a moral failing – created a culture where people could put down a dollar and borrow ten more to buy stocks at brokerage houses that, as Sorkin puts it, “sprang up on street corners the way Starbucks does today.” The democratization of private equity, venture capital, and crypto assets championed by the Trump administration echoes those choices.

Sorkin’s warning isn’t that history repeats itself, but that its patterns recur in new costumes. Today’s private credit funds echo 1929’s unregulated lending. Crypto tokenization mirrors the speculative investment trusts of that era. AI mania parallels the radio revolution. And tariffs, “the first domino” in 1929’s collapse, are again being deployed despite their well-documented tendency to trigger cascading failures. (As the saying goes, history doesn’t repeat, but it does rhyme.)

Yet Sorkin resists doomsday fatalism.

It does not have to happen again. We are not destined to have this happen again. It is true that the train is careening towards some form of a crisis at some point. The problem is you’ll never know. We’re always living in a bubble of some sort. And it will pop at some point, too. What we want to do, though, is prevent it from popping in such a way that it creates the next Great Depression. And I think that can be avoided.

The lesson he draws from 1929 isn’t that crashes are inevitable, but that the response matters most: the policies and choices made in the wreckage determine whether we face a correction or a Great Depression. Indeed, he perhaps consciously echoes Tuchman and JFK: “I like to say that I wrote this book almost as a prequel to Too Big to Fail (his bestselling story of the 2008 crisis) in hopes we don’t ever have to write a sequel.”

This is the kind of history that might prevent catastrophe rather than merely record it. That makes it worth reading. It’s a bit unsettling that there is no table of contents (I love getting the big picture first) and sort of reassuring that there are over 100 pages of notes and references, plus a nice discussion of the resources Sorkin got access to that had never been tapped before. Folks who would appreciate a bit of immediate access might watch a purely excellent PBS interview from Amanpour & Company (from which many of the quotations above are drawn) or read a transcript of Katie Couric’s interview with Sorkin.

This is the kind of history that might prevent catastrophe rather than merely record it. That makes it worth reading. It’s a bit unsettling that there is no table of contents (I love getting the big picture first) and sort of reassuring that there are over 100 pages of notes and references, plus a nice discussion of the resources Sorkin got access to that had never been tapped before. Folks who would appreciate a bit of immediate access might watch a purely excellent PBS interview from Amanpour & Company (from which many of the quotations above are drawn) or read a transcript of Katie Couric’s interview with Sorkin.

I’ll note in passing that the link to Mr. Sorkin’s book leads to Bookshop.org, an Amazon competitor launched during Covid. Bookshop’s business model is unique and admirable: they channel much of the profit from each sale to local independent booksellers. Like Amazon, they secure price discounts from publishers. Unlike Amazon, they do not offer free shipping to members who … well, pay hundreds a year to secure “free” shipping. There was a time during which Jeff Bezos seemed to be an exemplary business leader. That time is well past, and adding to his quarter-trillion-dollar fortune strikes me as abhorrent. So I don’t.

Most people don’t know that borrowing money was long regarded as a sign of moral failure. Governments didn’t, businesses didn’t, individuals didn’t. Much of Sorkin’s tale is driven by the concerted efforts to make being in debt normal, whether it was debt to buy cars or leverage debt to buy stocks. One of my Augustana colleagues, Lendol Calder, wrote a fascinating history of the domestication of debt, Financing the American Dream: A Cultural History of Consumer Credit (2001). A fine and careful work, well worth borrowing from your local library (if not going into another $72.45 debt for).

Michael Burry, the Big Short guy, just added his voice to the anxious chorus.

Mr. Burry is a hedge fund manager famous for anticipating the 2008 crash. And also famous for his annual apocalypses since. In the summer of 2021, he sounded the alarm on the “greatest speculative bubble of all time in all things” and in late January 2023 tweeted the single ominous word “Sell.” He left Twitter (and his 1.4 million followers) shortly thereafter. He returned at the end of October 2025 with an evocation of the movie “War Games.”

Really, not quite sure what to do with one-hit wonders. Elaine Garzarelli dined for decades on her call of the 1987 market crash without … well, ever being particularly right again.

Thanks!

To our bedrock supporters, Greg, William, S & F Advisors, William, Stephen, Wilson, Brian, David, Doug, Altaf: Thank you. We are genuinely humbled by your ongoing commitment. And, to George from PA, Thomas also from PA (Go Stillers and/or Iggles!), John from Pensacola, Mitchell from WA, Craig of Tennessee (hmm… several Red states have purpled-up; cheers to the Bears except, of course, in encounters with the aforementioned teams), Christine and Peter from WA, and, as ever, Leah of MA (I’ve been flirting with retirement myself but, so far, she won’t even make eye contact much less give me her number (sigh)).

Chip and I have substantially increased our support for the Riverbend Food Bank, which provides support for our region’s little food pantries and sustenance to an increasing number of our neighbors. (I tried to volunteer, but they need folks during retired-people time.) Cheers and thanks, especially, to the volunteers at 16 local Quad Cities high schools. As participants in the 39th Student Hunger Drive, the kids collected enough for 926,393 meals for the River Bend Food Bank’s 23-county service area, setting a new record. This was an increase from last year’s 786,186 meals, which I mention just in case you’ve defaulted to mumbling “kids these days,” and “Gen Z stares,” and “complete disconnection.”

Finding an answer to a child who says, “But I’m still hungry,” is something no one ought to need to do. Consider working with your local food bank or Feeding America. You will never see the faces of those you help, I know, but you will give hope as much as a meal.

As ever,